Promoting Self-Efficacy in McGraw Hill’s Digital Curicullum

Client

Toddlers Can Read

Sector

App Design, Education, Parents, Motivation

My Role

Design and Development Lead

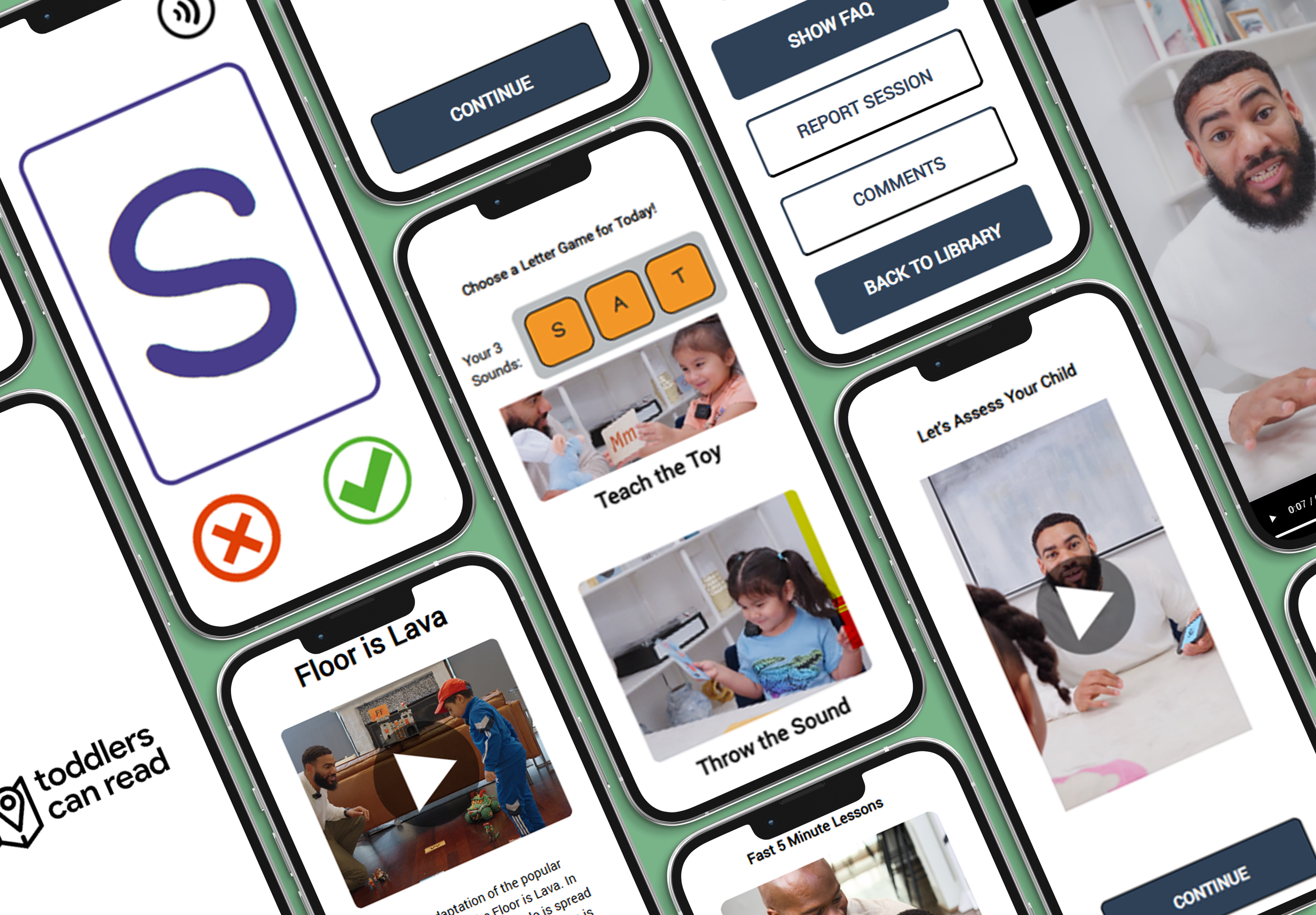

Spencer, founder of Toddlers Can Read, has a strong vision: empower parents to help their children with literacy. He had an educational video library, but he wanted to see higher adoption and success rates. He believed an interactive app would help inspire parents to action.

Design Review of Current Offering

We started with a design review. With my decade of experience building introductions to online tools, I could see some clear opportunities for improvement.

Example Design Principles

-

Asking mothers to watch two hours of video before they begin can be daunting.

-

A video was provided with a montage of activities, but it was unclear which activity parents should do and how.

-

The video site gave more videos as parents completed videos, but parents do not have goals around completing videos. Their goals are around teaching reading.

Brainstorming and Designing Prototype #1

All staff met in Dallas and brainstormed what an ideal app might look like. I emphasized listening to team members and making their ideas tangible. At the end of the brainstorming, we had Prototype #1.

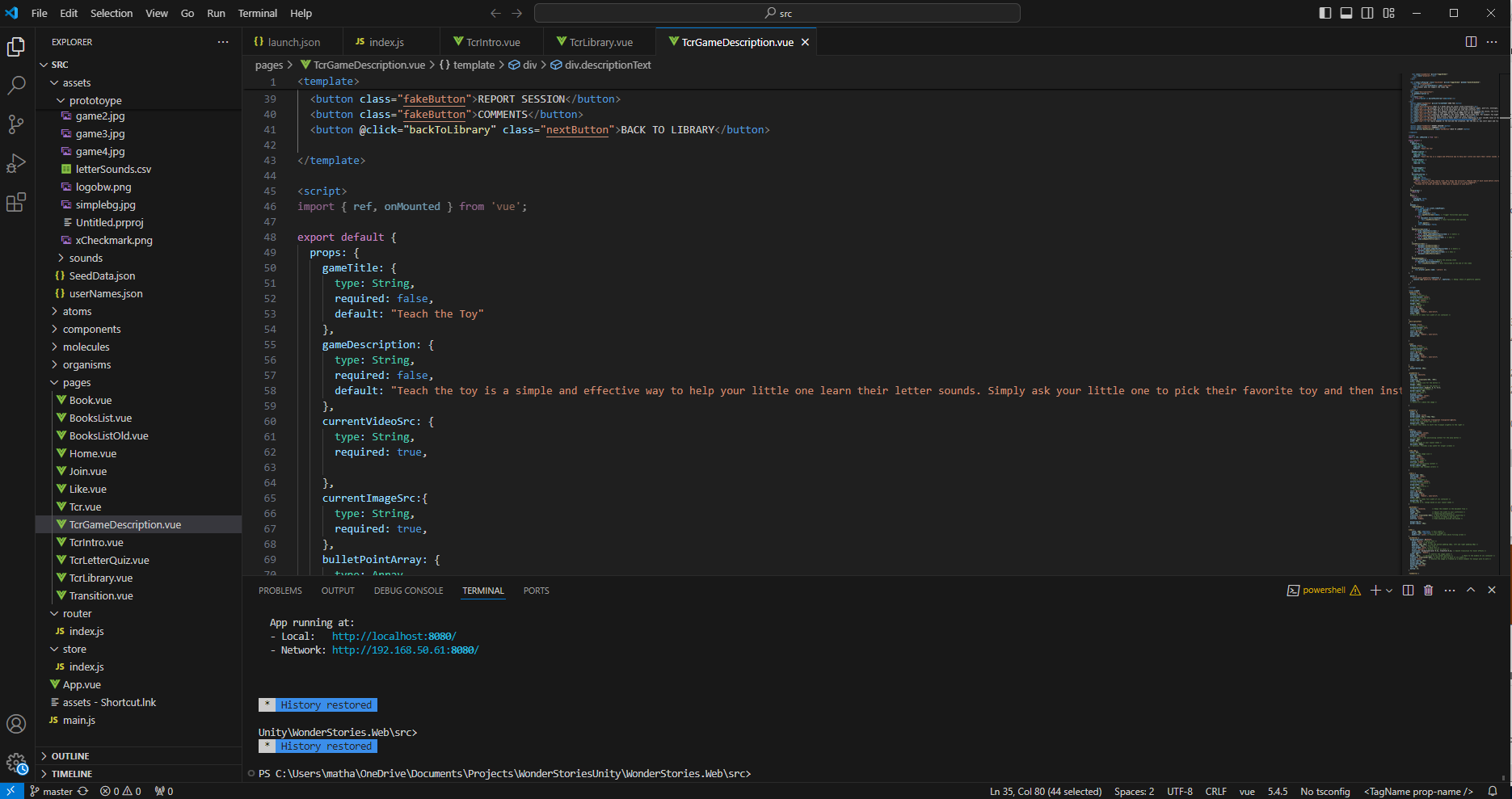

Build Digital Prototype

Using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, I built a digital prototype of the team’s idea. We needed an app that could be easily shareable (which meant it needed to be on the web) and we needed the app to adapt to the child’s diagnostic test — so it could not be static (e.g. Figma).

Link to prototype app we sent to parents (best viewed on mobile)

At-Home Prototype Testing

“Ask a mother if she wants to help her child read, and she will most likely say yes. Give a teaching app to a mother, and it will most likely never be used.”

I knew mothers’ social bias (they want to be good parents) would prevent us from understanding their real pain points. We also knew if we instructed parents to use the app, they would, as they would have felt forced to perform. So we sent the app to parents “as a bonus” for helping us, never asking them to use the app.

During our open-ended interviews, we asked parents to tell us what happened and why they did or did not use the app.

Co-Creation During Interviews

For many parents, they did not use the app daily. In prototyping, this was to be expected. We wanted to discover what was getting in the parents’ way. We worked with each parent to redesign the app in a way where they would want to use it each day.

Updated Prototype #1 During Parent Interviews

Research Findings

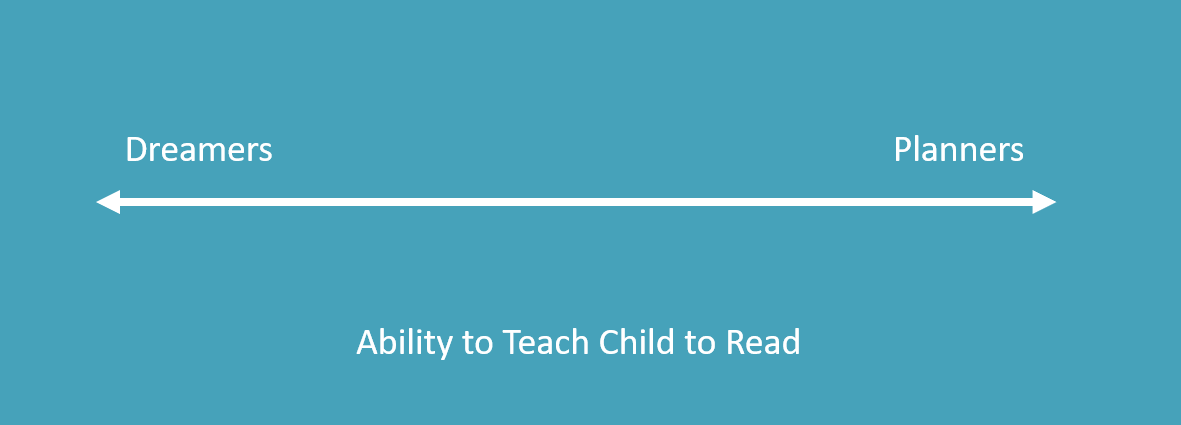

Spencer’s product had two distinct user profiles. Planner parents were masters at realizing their goals with their children: the type of parents who have the whole day scheduled, have looked at every teaching reading service, and most likely are stay-at-home. Spencer’s first product (and, in many ways, Prototype #1) was geared toward the planners — giving them a flood of information to help with their master plan.

The much larger profile are dreamers. They want to help their children prepare for school, but when an obstacle arises (e.g. “I don’t know where to start”), they give up. Their path needs to be clear to proceed. The vast majority of Spencer’s potential users are dreamers.

Design Principles to Help Dreamer Parents

-

There are a million things we need to know to be the perfect parents, and we can’t learn them all at once. The best way to learn is in the moment, through practice, and in bite-sized chunks. On Day 1, the parent may watch an introduction video. On Day 2, they may make flashcards. On Day 3, they may play a fun game with the flashcards with no learning objectives. What is the minimal learning a parent has to do each day to feel successful?

-

When I worked with i-Ready, we first introduced how to play a game before we taught a new skill (teach one thing at a time). Not only does a parent have to teach a new skill (phonics), but they also have to learn how to create structure around new learning games. Parent apps should have parents practice creating routine and game structures before starting to introduce educational content. Start by having kids practice animal sounds or shapes.

-

When I was designing a medical manual that instructed patients to “Insert 3 to 5 ml of insulin in the needle,” the patients became confused. “Is it 3 or 4 or 5? How am I supposed to make a choice?” While choice may feel empowering as a designer, it often paralyzes and removes parents’ confidence.

In our app, we asked parents to choose between four different games to play with their child (it didn’t matter which one they chose). Parents had to watch vidoes for all the games and then were not sure which one they should do. What sound should they work on? How long should they play? Are they making the right choices? None of these questions were critical, but they each created a moment of doubt for the “dreamers.”

Parents wanted the opposite of choice: “Just tell me that I am playing The Floor Is Lava while working on the ‘B’ sound.” They wanted to open up the app and have an activity ready to go with their child — no thinking or choices required.

-

There’s no way for Spencer to know every parent’s situation. A common worry was “My kid has a lot of energy, and you probably did not account for that.” While mothers do not want to have to think about daily exercises, when they do see the need for a change, they need to be empowered. If the activity today is “Teach your doll” but Mom needs her son to run around, she needs to be able to switch activities. So while everything starts as directed, parents need to be able to modify the lesson with additional, optional effort.

-

The TCR team thought a helper bot could answer questions parents might have, such as, “My child is not engaging; what should I do?”

We put a FAQ section in the app, and no parents read it. Asking an app for help is like making a choice — it requires thinking, energy, and planning, which our “dreamer” parents didn’t want.

However, they were all excited about the app working in the background making those activity choices for them. “Our algorithm sees that your child has mastered the ‘S’ sound, and we recommend you to move on to ‘M.’” This type of AI that doesn’t require input but provides clear, intelligent direction was viewed as the best feature for our future prototype.

-

Parents don’t want to fight with their kids to learn how to read. The #1 determinant of if a parent will use the app is if their child loves it and asks to play again.

In reality, many things that make learning fun are on the parent. Is Mom excited? How does Mom handle failure? How does she celebrate successes? We need to help Mom sell our app. We know this “fun factor” is critical for the app and will be prototyping new ways for apps to empower parents to make learning fun.

Empowering Parents Requires Critical Design Research

This research study was a small, weeklong study looking at how to empower parents. What I have learned is that the future of learning can and should be in parents’ hands. While parents are not expert teachers, that one-on-one time with early readers is so much more impactful than in the classrooms I work at with 30 children who are all behind and don’t want to be there.

But the future of reading can only be in parents’ hands if they are empowered. Future design should look to remove the requirement of having to be an expert in academics, planning, and entertaining. We need parents to feel that they can just push Play and they will be the Supermom. And I 100% believe moms can be the Supermoms when it comes to literacy — we just need design apps to help them believe in themselves.